WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

Irrespective of the content, does it matter that the people you watch online or real? If the answer is no then those real people are out of jobs in the future.

Interested in the Exponential Future? Join our XPotential Community, future proof yourself with courses from our XPotential University, connect, watch a keynote, or browse my blog.

Interested in the Exponential Future? Join our XPotential Community, future proof yourself with courses from our XPotential University, connect, watch a keynote, or browse my blog.

Who’s your favourite news reader? Are they human? That last question might sound odd, but thanks to the commercialisation of DeepFake technology we’re now reaching a point, as predicted, that means soon you won’t be able to figure out whether the person you’re watching on TV, or your favourite social media channel, is real or not.

Avatars, DeepFakes, digital humans, virtual influencers are all different types of technology, but increasingly they’re all being used for the same purpose – to replace real humans, from pop stars to influencers, as well as teachers and university lecturers, with digital dopplegangers.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been coming for journalism for some time thanks to the rise of robo-journalists like OpenAI’s GPT-2 that can write their own news content, which can now be read by Reuters fake newscaster, and recently Chinese TV unveiled the world’s first AI newscaster. And now Reuters, following in their footsteps, have unveiled their own fully automated DeepFake presenter in an effort to show that AI can be used to enhance the scale and personalisation of news in ways that were previously unimaginable.

This is all fake … DeepFake tech and it looks “real”

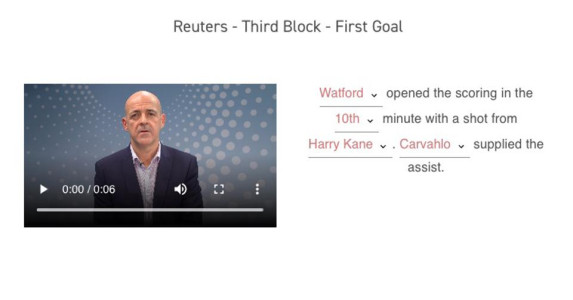

Developed in collaboration with London-based AI startup Synthesia, who also produced the David Beckham DeepFake I reported on a while ago, the new system harnesses AI in order to synthesize pre-recorded footage of a news presenter into entirely new reports. It works in a similar way to DeepFake videos, although its current prototype combines with incoming data on English Premier League football matches to report on things that have actually happened.

“The system has two parts,” says Nick Cohen, Reuters’ Head of Core News Products. “Firstly, we use an algorithm to combine Reuters real-time match photography and reporting with a minute-by-minute data feed of what has happened in the game. This allows us to automatically generate a script for any match report, combining the words describing the event with the relevant picture.”

Reuters already uses algorithms and live data to create text-based summaries of football matches and other sporting events. However, as Cohen explains, the difference with their new system is that it combines with Synthesia’s AI-based synthetic media platform to synthesize videos of a human presenter reading match reports.

“Secondly, we then worked with Synthesia to film our sport editor, and used their technology to create an AI generated version of him who can ‘read’ any version of the script within the set parameters.”

In other words, having pre-filmed a presenter say the name of every Premier League football team, every player, and pretty much every possible action that could happen in a game, Reuters can now generate an indefinite number of synthesized match reports using his image. These reports are barely indistinguishable from the real thing, and Cohen reports that early witnesses to the system (mostly Reuters’ clients) have been dutifully impressed.

But how exactly does Reuters’ and Synthesia’s new system exploit AI? Well, according to Synthesia’s CEO and co-founder Victor Riparbelli, it revolves around the use of digital twins and generative adversarial neural networks.

“The system uses AI to first analyse the video and build a digital copy of the presenter,” he tells me. “This is much like you would do in Hollywood to create a digital character (think Benjamin Button or digital characters in sci-fi flicks), but rather than taking months or years to create a scene we are able to do this in a matter of hours.”

Riparbelli adds that, by utilizing machine learning, and in particular generative adversarial networks, “we can train our system (rather than manually instructing it) to accurately simulate new video of the presenter. And we can do this in a matter of hours, not months or years.”

The results are very impressive. But the advantage of Reuters’ and Synthesia’s system isn’t only that it can produce realistic, ‘DeepFake-style’ simulations of a real-life presenter, but that it can be deployed at the kind of scale you couldn’t possibly match with human newsreaders. Potentially, you could have presenter-led video reports on every football match in the UK, Europe or the entire world, delivered all-but instantly after each match ends, or even at any point during play. The possibilities are almost endless.

“The results have been quite an eye-opener and show us the potential and the quality that’s now possible with synthetic media,” Nick Cohen says. “For Reuters it is fascinating to see how our real-time feeds of photography and reporting can now be combined with these new kinds of technology to deliver news and information in new ways.”

Reuters says that the system it has developed with Synthesia is still at the prototype stage, and is still being used to report solely on football matches. Nonetheless, Cohen affirms that the news organization is open to the possibility of deploying it at scale, and in other areas besides sport.

“While this is still very much a prototype, we’re really excited about exploring any new ways we can use Reuters real-time pictures, reporting and data feeds to power new kinds of AI-driven news experiences,” he says. “The technology to do this is already here, but we would want to fully explore the ethical and consumer understanding issues involved before we release a real-world product.”

As for those ethical issues, there’s the collective dislike much of the public has for DeepFake videos, although both Synthesia and Reuters confirm that theirs isn’t a DeepFake system, since it will be used to report fact. But even assuming that some other company or companies doesn’t use similar tech to create ‘fake news-style’ synthesized video reports, there’s also the question of what this tech means for the future of journalism.

For Victor Riparbelli, the new system will be a complementary addition to traditional news reports with human presenters. And what’s perhaps most interesting about the system, is that it will let Reuters achieve both massive scale and also finely grained personalization on the other.

“I don’t see this as being an alternative or replacement for the six o’ clock news,” he says. “Rather I see this as a tool that enables broadcasters and companies to produce the video content and personalised procedural content that their audience demands.”