WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

As researchers begin experimenting with the electromagnetic spectrum and higher frequency sounds they’re finding new ways to track disease.

Interested in the Exponential Future? Connect, download a free E-Book, watch a keynote, or browse my blog.

Interested in the Exponential Future? Connect, download a free E-Book, watch a keynote, or browse my blog.

As the deadly Covid-19 coronavirus wreaks its havoc around the world perhaps one of the biggest issues people face is the fact that they don’t know whether or not they’ve already been in contact with someone who already has the disease, and whether they’re subsequently infected. And while there’s no way to tell right now, other than to have a difficult to obtain test, or get scanned by a drone, one of the questions I’ve been mulling over in my head is whether we’ll ever be able to detect and identify the viruses in our immediate vicinity using nothing more than a smartphone or smart gadget so we can protect ourselves from coming into contact with the infections in the first place – something that, at the moment, South Korea are trying to do by offering their citizens smartphone apps that track how close they’ve come to infected people and infected zones.

As stupid a question as this might sound we’ve already seen spectrometers put into smartphones, and the development of new Terahertz technologies that could analyse biological content at the nanoscale, and new quantum sensors that are millions of times more sensitive than today’s sensor technologies so the answer, one day, might be “Yes.” So that’s why this new innovation caught my eye – the ability to use sound to identify the track of disease, in this case Cancer.

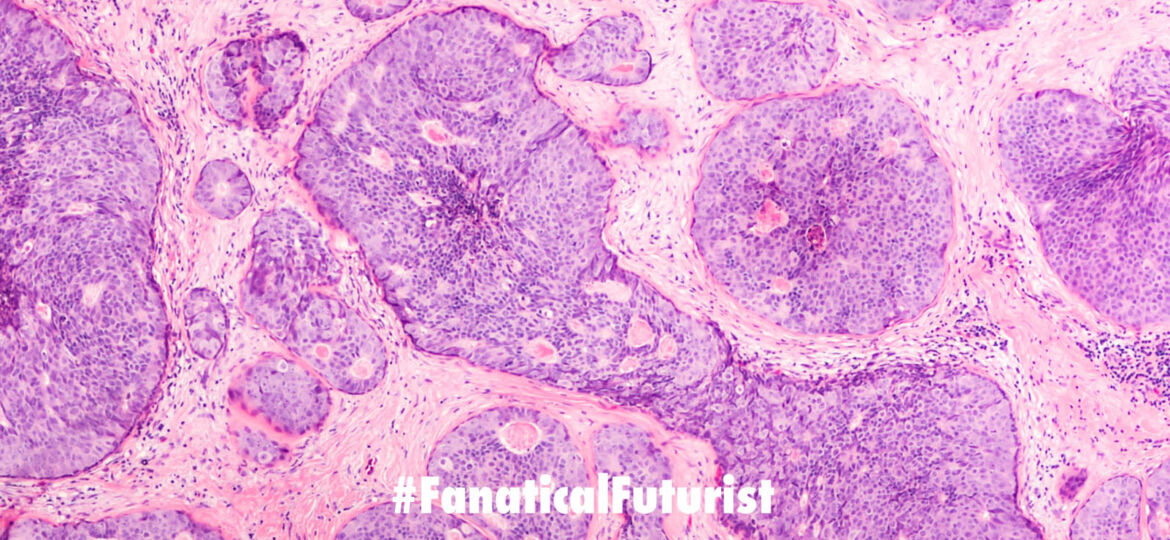

One physiological consequence of cancer and other diseases spreading throughout the body can be the hardening of the structure surrounding cells called the extracellular matrix. Scientists at Purdue University have now developed a new way to detect such changes through the use of sound waves, offering a potential new tool to track disease progression.

The stiffness of the extracellular matrix surrounding cells may alter in response to toxic substances, drugs and disease, and scientists are hopeful of tracking tiny changes to this structure as a way of monitoring patient health and the spread of disease. Possibilities have included applying chemicals to samples of the extracellular matrix, or stretching or compressing it to measure any changes within, but this has proven hard to do so without causing it damage.

The Purdue University scientists believe they have found a way around this, with a small Lab-on-a-Chip device. This consists of a transmitter that generates an ultrasonic wave, which is propagated through a sample poured onto the platform, and a piezoelectric receiver on the other end. The electrical signal that the receiver generates is shaped by the stiffness of the sample, and can therefore reveal changes to its structure.

“It’s the same concept as checking for damage in an airplane wing,” says Rahim Rahimi, a Purdue assistant professor of materials engineering. “There’s a sound wave propagating through the material and a receiver on the other side. The way that the wave propagates can indicate if there’s any damage or defect without affecting the material itself.”

The team put its lab-on-a-chip through its paces in experiments involving breast cancer cells embodied in a hydrogel, which was chosen for its similarity in consistency to an extracellular matrix. This revealed changes in the stiffness of the simulated tissue, and did so without inducing a toxic response in the cells or overheating the device.

According to the team, the device could be scaled up and used to analySe a number of samples at the same time, which would allow scientists to study different aspects of a disease. They have now moved into testing extracellular matrices based on collagen, the key structural protein in skin and other tissues.

A research paper describing the device was published in the journal Lab on a Chip, while you can hear from the scientists involved in the video above, and while our ability to use a tricorder-like device to scan our immediate environment for diseases like Covid-19 is still a long long way away I’m slowly seeing, possibly, the technologies we could use to accomplish it. So check back in about a decade or two…