WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

The more organs scientists can create outside of the human body the greater the benefits to human healthcare, this latest breakthrough takes us another step closer to realising the potential of regenerative medicine.

When scientists want to understand how a drug works, they often turn to mice or other small animals to see how it works in them, then try to relate the results in humans. But a mouse is not a human, and its body functions quite differently. So for a few years now, researchers have been working on a better approach – tiny organs, called organoids – that grow and live inside a petri dish, but that function like an actual organ.

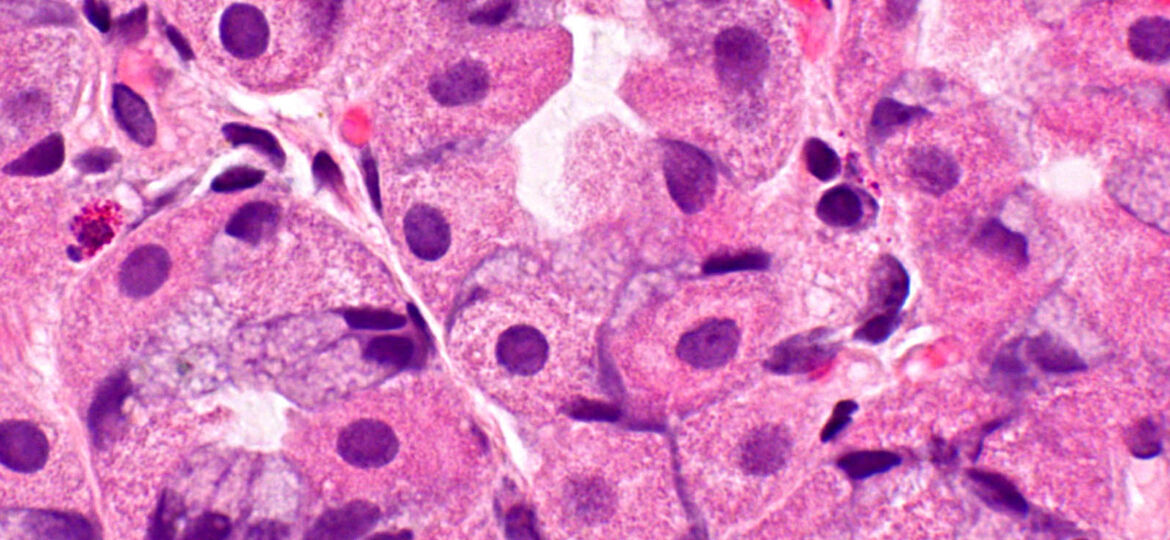

This week researchers at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center announced that they’ve managed to use pluripotent stem cells, stem cells that can be directed to grow into any other type of cell, to re-create a piece of working piece of human stomach – complete with the ability to produce acid and digestive enzymes – in a petri dish. And they say that it will help them to better understand how the real thing works, and what exactly happens when things go wrong.

The human stomach has multiple sections, all with different functions, and the researchers recreated a section of the stomach called the fundus, which is responsible for producing the acid and digestive enzymes necessary to break down the food we eat. But this vital section of the stomach is also particularly vulnerable to disease. Too much acid can create acid reflux disease, while an infection with the bacteria H. Pylori can cause ulcers and inflammation. By studying how these diseases progress in the stomach tissue, the scientists hope to be better equipped to treat them.

“You can watch diseases unfold under a microscope,” says James Wells, the lead author of the study, “and now we can see how the stomach heals itself.”

For example, when too much acid builds up in the stomach, it often inflames the inner stomach lining. Certain drugs, like Prilosec, treat this inflammation by reducing the amount of acid your body produces. Seeing this healing process in action and what contributes to it, Wells says, gives researchers the opportunity to find new, and potentially better, methods for healing it – whether that’s with drugs or with tweaks to the gut’s microbiome. Their work was published this week in Nature.

This discovery comes two years after the researchers created another area of the stomach, the antrum, which is responsible for producing hormones that perform vital tasks like stimulating appetite using a similar technique.

The ultimate goal for many of the scientists in this field though is to create what’s known as a Human on a Chip, a small credit card sized device that will allow scientists mix and match different organoids together in order to mimic the natural workings of the human body. And while some of these chips already exist, such as Heart on a Chip and ten other organs, it’s thought that these chips, once mature enough will then allow scientists to run drug simulations quickly, and “in vitro,” without the need for animal testing.

One day these chips, and this research, could even help to herald in a new era of regenerative medicine, where army field medics, doctors and scientists could grow and 3D print transplantable, personalised replacement organs from patients own stem cells that can one day be transplanted into their bodies without the need to wait for organ donors. But that work is at least a few years down the line. For now, these organoids will earn their keep by helping scientists make our guts a little less mysterious.