WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

As our ability to create and control plasma in new science fiction like ways improves so too does our ability to create new sci fi devices.

Interested in the future and want to experience even more?! eXplore More.

Interested in the future and want to experience even more?! eXplore More.

The world of science fiction is quickly becoming science fact, from real, working holograms, laser weapons, memory downloading, editing, erasure, streaming, transfer, and uploading, molecular assemblers, tractor beams and telepathic communication devices, to prototype deflector shields, and teleporters, even through to theoretical warp drives. But one science fiction technology has so far eluded us – until now. I am, of course, talking about Star Wars light sabres.

Nothing says welcome to the future like having your wound fixed by a tiny light sabre, and it might sound wild at first, but that’s what a new plasma technology breakthrough has now demonstrated.

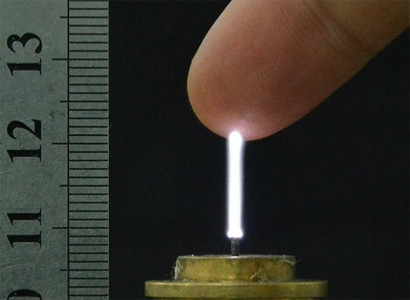

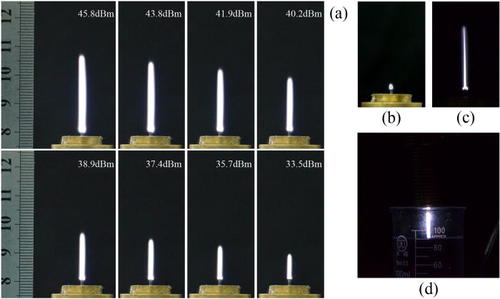

Courtesy: UESTC

This exciting development means we could soon commercialise low-temperature Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Jets (APPJs) that operate out in open air, promising a new age in medical treatments. And yes, APPJ’s, in case you were wondering, are the scientific community’s official, and boring, name for light sabres. Still though, light sabre sounds cooler than an “APPJ device.”

Engineers from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China have found a way to unleash a flow of microwave-generated ions so it extends far enough to touch nearby surfaces.

If you’re not sure what atmospheric pressure plasma is, the most important parts are in the name.

Unlike directed streams of charged particles that can only be produced in a vacuum or under intense pressures, this plasma is made of supersonic blobs of stable gas, or ‘plasma bullets’, that don’t require a specific pressure.

There are a variety of ways they can be produced, such as by exciting particles with different currents or low-frequency electromagnetic radiation – such as microwaves. But all of these bullets can be pumped out at rather benign temperatures, lending them to a variety of heat-sensitive applications that could use streams of ions.

Engineers can use bundles of tiny APPJs to ionise the surfaces of materials, for example. Physicians could also use them to sterilise wounds, clean teeth, and even help blood coagulate.

“With the development of low-temperature plasma jets, the applications of plasmas used in biomedical fields would be extended for use not only as a surgery knife, but also for skin treating, sterilisation, and cancer therapy,” says engineer Wenjie Fu who led the research.

There’s just one tiny problem. Until now, these plasma jets tended to suffer from a frustrating limitation – to stabilise their flow, you’d need a polarised tube made of a material such as quartz.

This would be like wrapping a lightsaber in a clear plastic tube to keep it contained like the toy ones you can buy in the shops – not entirely practical or desirable.

To do away with such a tube container without raising the jet’s temperature, researchers ditched the kinds of microwave guides other devices used to generate the plasma and turned instead to a coaxial cable type structure.

Tinkering with the distances between the conducting elements in the lines, they could increase the electric field density of the microwaves without adding power.

A few critical adjustments to the end of this coaxial transmission system also allowed them to channel a gas around the outside and the plasma down the centre, allowing them to ditch the quartz tube and still tune the gas’s characteristics.

The result is an exposed, directed stream of plasma that can kill microbes and coagulate blood, and is cool enough to touch; or it can be ramped up to incinerate flesh – for surgical purposes or to defeat enemies. You choose.

It’s still early days for this kind of medical technology, but with the proof of concept now looking solid, a commercial version of such a ‘light scalpel’ could be in your doctor’s hands in the not-too-distant future. And then, perhaps in a decade or so you might be able to trade those toy light sabres in for real ones…

This research was published in Applied Physics Letters.