WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

Carbon fiber’s light weight and superior strength make it idea for many applications, but up until now it’s been expensive and very difficult to work with to create products, that’s all about to change.

Modern carbon fibre bikes, stiffer and stronger than their metal counterparts at literally fractions of the weight, are technological marvels. But they have two drawbacks. Firstly carbon fiber is incredibly expensive, although recently I discussed a new plant based, not oil based, carbon fiber process that might help bring those costs down, and secondly it’s a quality control nightmare. Now though one tech company aims to change all that with the innovation of 3D printing. and once the manufacturing process is refined this is a breakthrough that could one day see companies 3D printing carbon fiber cars, like this exclusive Lamborghini concept, buses, like this one called “Olly” by its creators, and all manner of other goods at scale.

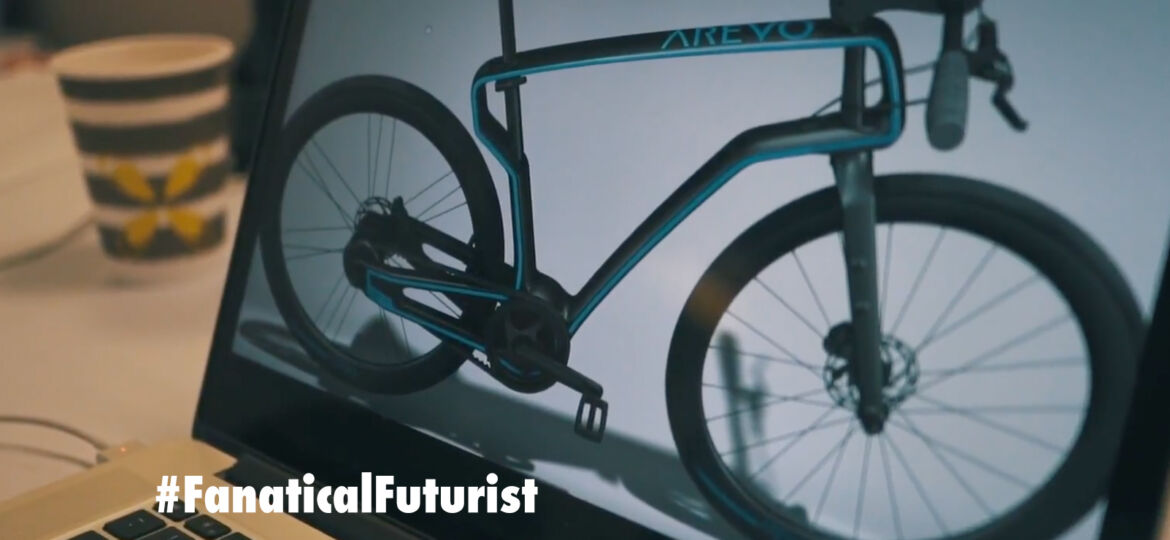

Arevo, a Silicon Valley start-up, whose tag line is aptly “The revolution will be printed,” has just showcased the world’s first 3D printed carbon fibre bike. While the sophisticated looking city bike is only a prototype, Arevo said it wants to move quickly into manufacturing by partnering with existing bike companies. Robotic production could reduce the chances for errors in construction that lead to frame failures. And, the company said, its technology makes carbon fabrication affordable enough that bike manufacturers could make cost competitive frames.

Watch the first of its kind bike being made

“We’re looking at a couple of types of bike, and we plan to be at Eurobike with a potential partner,” said Jim Miller, Arevo’s CEO.

Traditional carbon composite manufacturing is notoriously labour intensive, requiring human assembly and expert precision. Some high end frames can have as many as 500 individual pieces of carbon fibre. Arevo’s process differs in both construction technique and materials. Instead of laying down plies of fabric in a mould, a printer head mounted on a robotic arm lays down carbon-fibre filaments, swivelling to orient them into a full bike frame. The filaments are continuous carbon fibre, not the short, chopped fibre used to make parts like pedal bodies, which might be Arevo’s biggest manufacturing breakthrough.

The resin is different, too. Instead of a thermoset construction like conventional carbon fibre, Arevo’s composite includes a thermoplastic called PEEK which stands for Polyether Ether Ketone, which is used in industrial parts.

To Miller, manufacturing is only half the story. What makes the process possible is Arevo’s software for designing and analysing structural parts.

“We talked to the top simulation software companies,” he said, “and the ability to start with a blank slate and put carbon fibre strength anywhere in that approach – no one as far as we know of can do that in any composite part yet, let alone a bike.”

Colin Hughes, engineering manager for Ibis Cycles and, before that, carbon bike pioneer Kestrel, sees potential for Arevo’s technology. Prototyping could become far quicker, for one. The big factories in Asia that make most carbon bikes, he said, “are designed for production stability, and they don’t really want to change anything.”

Arevo’s process could offer companies, especially small or midsize brands like Ibis, the chance to prove a design works with less effort.

Miller said Arevo can work with almost any commercially available carbon fibre, as well as blends like Carbon-Kevlar. He also pointed out that thermoplastics have much better toughness and durability than thermoset carbon composites, which are more brittle and susceptible to cracking. And robotic production should dramatically reduce the variability that occurs for handmade carbon.

But it’s a long way from a prototype to production. The bike industry has tried thermoplastics before, but certain drawbacks have prevented it from becoming widely used, especially for frames. Weight is one issue. Years ago, GT tried making carbon-composite thermoplastic frames, Hughes recalled, “but they were always heavier than the metal bikes.”

While Arevo said it can get production costs low enough to compete with Chinese and Taiwanese made carbon, it’s still an open question as to whether the method can offer the performance benefits of conventional carbon.

Miller said he’s shocked by how well the Arevo prototype rides. But he admitted that right now, utility, E-Bikes, and bike share “are probably our lead opportunity. With a performance bike, we’re still refining our process. It may be an application, but not right away.”

That presents a higher economic hurdle, since most utility bikes today are made of metal, not carbon. Arevo must get at least close to cost-competitive with a material that’s far cheaper. But if it can solve some of the performance questions, Miller thinks Arevo could be a player in performance bikes, too.

“The most interesting aspect of this is the capability,” he said. “Imagine walking into a bike shop and getting custom-fitted to a bike and, because the supply chain is local and can print the bike quickly, you get that custom bike in a few weeks rather than months.”

Arevo has already attracted investment from well-known engineer and venture capitalist Vinod Khosla of Vinod Khosla Ventures, as well as a prior round of funding from In-Q-Tel, an investment arm of the CIA. The tech is scalable and can be used for everything from car parts to airplane wings. The company does plan on pursuing other markets. So, for its first showcase product, why a bike?

For starters, a bike is a large, complex object, and therefore a good test subject for manufacturing capability. But more than that, it’s a bike.

“When people see a bike, whether they’re an investor or someone in the bike industry or aerospace, everyone knows what it is and gets excited,” Miller said, “nothing captures the imagination like a bike.”