WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

As we learn more about manipulating the human brain companies are starting to find new ways to hack it to treat common diseases.

Love the Exponential Future? Join our XPotential Community, future proof yourself with courses from XPotential University, connect, watch a keynote, or browse my blog.

Love the Exponential Future? Join our XPotential Community, future proof yourself with courses from XPotential University, connect, watch a keynote, or browse my blog.

Over the past couple of years there has been more and more research into using neuro-technology, which includes everything from Brain Machine Interfaces (BMI) that are surgically implanted into people’s heads and packed into smart glasses and smart tattoos, to memory downloading neuro-prosthetics and TMS devices, that augment, manipulate, and modify human brain waves and signals to boost everything from people’s ability to learn new skills faster, improve sports performance, and play telepathic games. And now a new company from the US, Nēsos, which just came out of stealth mode, is using similar technology to try and find new ways to treat a range of common diseases.

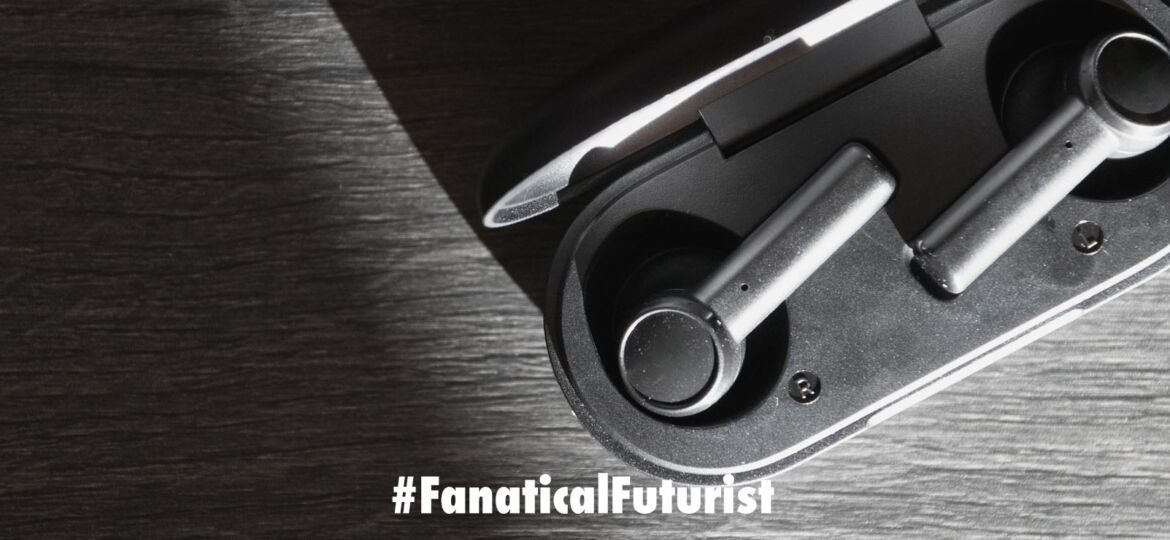

While the company’s new devices might look like regular earbuds they don’t play music or produce any kind of sound – instead, they generate electrical fields designed to treat disease.

By delivering electrical pulses to a nerve in the outer ear they hack into neural circuits in the brain in a way that could help regulate inflammation and treat rheumatoid arthritis.

Courtesy: Nēsos

“We’re still at the early stages of development,” says Konstantinos Alataris, co-founder and CEO of Nēsos. “We’re developing this as a prescription product and testing it in clinical trials.” And arthritis is just the first application that the startup is pursuing. If Nēsos has indeed found an effective way to hack into the brain then their unassuming earbuds could very well help treat a range of neurological and psychiatric diseases.

The results of the company’s first in-human study were presented last month at the American College of Rheumatology 2020 meeting. In that study, 30 people with rheumatoid arthritis were instructed to use the earbuds for a few minutes a day, for three months.

By the end of the study, half of the volunteers had improved in a clinically meaningful way. More than half of those patients who benefited showed a 20 percent improvement, a third improved by 50 percent, and a few patients experienced a 70 percent improvement in symptoms.

Nēsos’s device taps into the power of the vagus nerve – the meandering superhighway of the nervous system that connects the brain to key organs in the body. This nerve has been the subject of a wide range of research. Scientists have tried modulating it to treat all sorts of maladies, including migraine, stroke, heart failure, depression, and inflammatory problems such as Crohn’s disease, with varying degrees of success.

This kind of treatment, called neuromodulation, typically involves surgically implanting a stimulation device with electrodes that directly touch neural fibers. Electrical impulses are then sent to the vagus nerve to change the communication between neurons.

The company SetPoint Medical, for example, has had some success treating rheumatoid arthritis with an implanted device that stimulates a subset of vagus nerve fibers in the neck. Researchers have found that stimulating those fibers activates cells in the spleen that ultimately block the production of inflammatory molecules called cytokines. The treatment reduces inflammation, and that’s exactly what people with rheumatoid arthritis need.

Nēsos’s device targets the same pathway, except with a completely non-invasive device that fits in the ear like an earbud. And instead of targeting the vagus nerve in the neck, the earbuds, through the auricular branch of the vagus nerve, send electrical impulses to brain regions believed to regulate spleen output and the immune response.

“Fifty years ago, we thought that the brain and the immune system were independent,” says Alataris. “Now we know that they’re in constant communication and interaction.”

Surgically implanted stimulation devices tend to be more precise than non-invasive devices, such as earbuds, that don’t break the skin and can’t make direct contact with the targeted neural fibers. But surgical neural implants are typically reserved for people who have exhausted most of their treatment options, or are in late stages of disease. A non-invasive device, however, allows Nēsos to try the therapy on people in earlier stages of disease, says Alataris.

Nēsos is now starting on a larger human study that will compare the effects of the device on people with rheumatoid arthritis and a control group. The company is also testing its technology in people with postpartum depression and migraines.

Rigorous clinical studies are necessary if the company wants to get regulatory approval as a medical device and claim that its technology treats disease. That kind of data will also differentiate Nēsos’s device from the growing number of stimulating earbud and headphone products on the consumer market. Makers of these devices often claim their devices improve “wellness,” but lack rigorous science to back up such statements.

Nēsos will be backed by data, Alataris says. “As long as the data supports it, we will keep going,” he says. “And so far, the data tells us to keep going.”