WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

The Internet of Things relies of billions of sensors to work, but only a handful of these sensors can be powered with traditional batteries, so new alternatives are needed.

In remote parts of the world, access to batteries for diagnostic devices, medical equipment and other so such products is often limited. Paper based biosensors have long been used in these environments, but without a power source, they generally lack enough sensitivity to provide accurate results that are so often needed in those situations. As a result researchers behind the latest “energy breakthrough” went in search of a low power biological alternative that could power these sensors and other Internet of Things (IoT) connected devices.

“Paper has unique advantages as a material for biosensors,” said Binghampton University’s Seokheun (Sean) Choi, PhD, who presented the work recently at the American Chemical Society (ACS). “It is inexpensive, disposable, flexible and has a high surface area. However, sophisticated sensors require a reliable power supply, and commercial batteries are too wasteful and expensive, and they can’t be integrated into paper substrates. The best solution is a paper based Bio-Battery.”

The new Bio-Battery

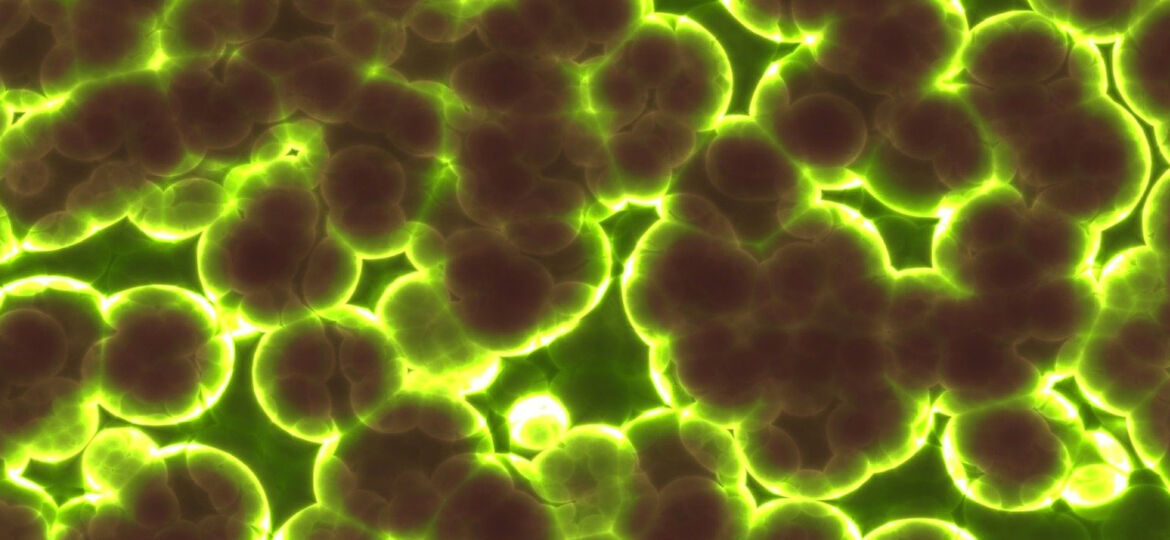

To create the bio-battery, the team first printed thin layers of metals and other materials onto a paper surface. For the power source, a quantity of freeze-dried bacteria known as exoelectrogens was then added. Exoelectrogens transfer electrons outside of their cell membranes as the bacteria produce energy for themselves, activated by water or saliva. As the electrons pass through the paper to the electrodes, enough power is generated to run a calculator and an LED. The team found that oxygen slightly diminished the power output, but as the exoelectrogens were tightly packed next to the paper, the effect was minimal.

The bio-battery, which is designed for single use, has a shelf-life of around four months though and Choi and his team are currently working on new methods of treating the bacteria to extend their survival and performance.

“The power performance also needs to be improved by about 1,000 fold for most practical applications,” he said, which is a big, but not unachievable, leap.

Choi has applied for a patent for the technology and is now looking to commercialise the device with the help of industry partners.