WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

One day aircraft will be fully autonomous, but getting there is a journey of many steps and this is one of them, and Boeing is placing its bets.

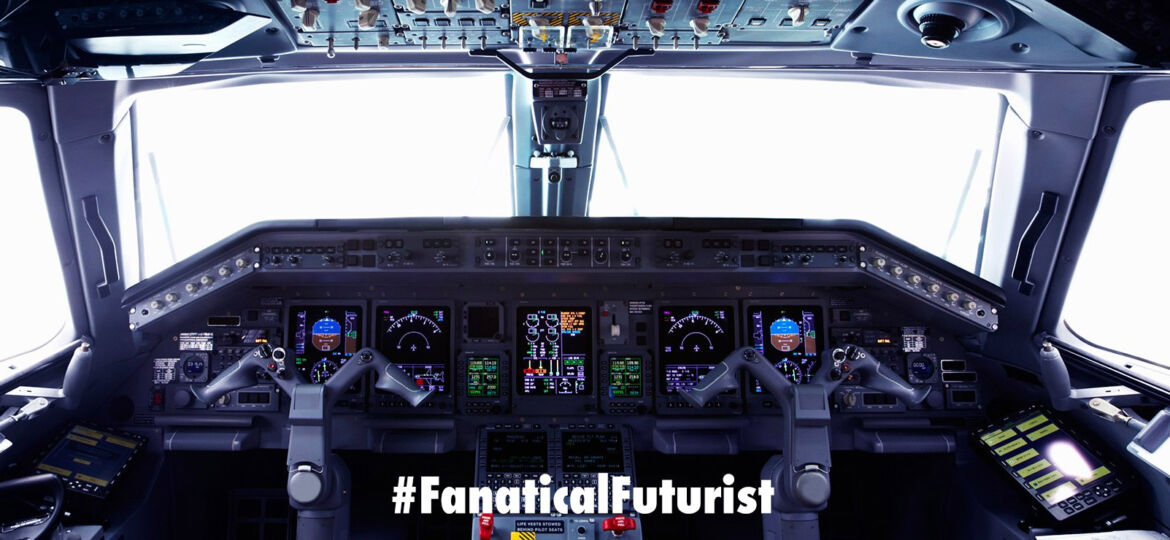

Everything it seems these days is going autonomous, from cars, trains and trucks, to giant cargo ships and pizza delivery robots. And, not to be left out, so too are aircraft, but unlike their other autonomous brethren you can’t just flick a switch and hope for the best, and the journey to fully autonomous aircraft, as first announced by Boeing last year, who are also building everything from rockets that will head to Mars to autonomous military subs and drones, the journey to realise their goal will be a slow and lengthy one.

In order to realise their ambition of safe, autonomous aircraft Boeing has now announced they’re actively working on technology that would remove the need for a second pilot in its passenger jets even though existing European aviation rules state that passenger planes with more than 19 seats must have a minimum of two pilots in the cockpit. But despite those regulations, and constraints, Steve Nordlund, a vice president at Boeing, said autonomous technology that would allow for a reduction in on-board crew was being developed at a “good speed.”

He also said Boeing “believes in autonomous flight and self-piloted aircraft” and the firm’s commercial aircraft division was “working on those technologies today”.

“I don’t think you’ll see a pilotless aircraft of a 737 in the near future,” he told reporters recently. “But what you may see at first is more automation and aiding in the cockpit, maybe a change in the crew number up in the cockpit.”

He suggested cargo jets could be the first to trial the technology but that it made “business sense” to pursue a reduction in the number of on board crew on passenger planes, too.

“A combination of safety, economics and technology all have to converge, and I think we are starting to see that,” he said.

It would also address a chronic shortage of pilots which analysts have said could reach more than 200,000 over the next decade. But while planes have become increasingly automated in recent decades, with autopilot routinely used throughout all phases of a flight, the prospect of fewer crew members may still prove to be a hard sell – both to passengers and regulators.

After a Germanwings pilot flew an A320 plane into the French Alps in March 2015, killing all 150 people on board, Europe’s Aviation Safety Authority, EASA, imposed a rule that two crew members should be in the cockpit at all times. It meant that if a pilot needed to step out of the cockpit, to use the toilet for example, a member of the cabin crew had to step in, then EASA relaxed the requirement last year, saying it was up to airlines to ensure their aircraft were safe.

Sully Sullenberger, the retired US Airways pilot who saved the lives of 155 people when he landed an A320 on New York’s Hudson River after both engines suffered a bird strike, has previously spoken out against moves towards single-pilot aircraft.

After the US Federal Aviation Administration asked Congress for money to research single pilot commercial airliners, he said: “Having only one pilot in any commercial aircraft flies in the face of evidence and logic. Every safety protocol we have is predicated on having two pilots work seamlessly together as an expert team cross-checking and backing each other up.”

Nordlund, who heads the firm’s innovation arm, Boeing NeXt, insisted single pilot crews would only be deployed if there was appetite for it from airlines.

He said developments would be driven by the “comfort levels of the consumer”, suggesting passenger concerns about safety – whether well founded or not – could delay the roll out of autonomous technology.

But he added: “When it is cargo, that aspect is taken out of the equation.”

Dr Rob Hunter, head of flight safety at the pilot’s union Balpa, said there had been a “steady reduction in the number of crew on the flight deck of commercial aircraft” but voiced concerns that a reduction in flight deck crew, would lead to a “greater number of occasions when the both the machine and the pilot becomes overwhelmed”.

“In the airliners of the post-war period there were up to six crew acting as pilots, flight engineers, navigators and radio operators. All of these roles are now undertaken typically by just two pilots that are, more-or-less, supported by automatic systems. Sully is absolutely right, to believe otherwise is to ignore the vital role the human plays in keeping things safe,” he said.

Airbus, Boeing’s European rival, is also developing its own autonomous technology to allow a single pilot to operate its commercial jetliners, but is first working on cutting the number of crew needed on long haul flights to just two.

EASA said it was “aware of discussions with aircraft manufacturers about possibilities to reduce the number of pilots in the cockpit of certain aircraft operations, including for cargo” but would not be drawn on how regulations could be altered to accommodate the new technology.

Talking of Boeing’s other plans Nordlund then talked about the company’s first hypersonic passenger jet concept in years which if realised could transport passengers at 3,900mph at an altitude of 90,000ft, around three times higher than existing subsonic jets, from London to New York in two hours.

“Engineers are working company-wide to develop enabling technology that will position the company for the time when customers and markets are ready to reap the benefits of hypersonic flight,” a statement said at the time.

Nordlund said hypersonic travel – at Mach 5, or five times the speed of sound – could become a reality within the next two decades.

He said it had the potential to take someone from New York to Tokyo for a lunch meeting before returning them home on the same day.

“Hypersonic travel is probably 10 to 20 years [away],” he said, but added: “There are so many technologies that need to be overcome.

“The technologies are maturing. Outside of having the propulsion to move at that speed, [Boeing is focused on] making sure that the cabin experience is one that is acceptable to passengers. I mean, can you imagine moving at that speed. And the materials that are needed for the aircraft to absorb the altitude that it will be flying at, they are all still in work.”

“There needs to be some modelling and simulation around the change of time zones, how would it work, and what time do you leave New York for that lunch in Tokyo? There is a lot of work still to be done on it [but] from an aircraft standpoint it is absolutely possible,” he added.

Boeing is also developing plans for a fleet of urban air taxis, like the ones being deployed in Dubai, which, it is hoped, would be used to rapidly transport passengers around some of the world’s most densely populated cities.

The plans allow for the aircraft to be piloted or autonomous and to use radar and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to guide them safely towards centralised landing pads, Nordlund said. He insisted this form of urban air transport, which Boeing is working on alongside Uber, who recently unveiled their concept flying taxi stations, was “absolutely” feasible.

“The next time you are sitting in traffic, just look up. What you see above you is open space. We have got to be working in those three dimensions to alleviate problems that exist on the ground.”