WHY THIS MATTERS IN BRIEF

Bacteria have some amazing capabilities and soon we’ll be able to harness them to help us 3D print and create new exotic materials and products like never before.

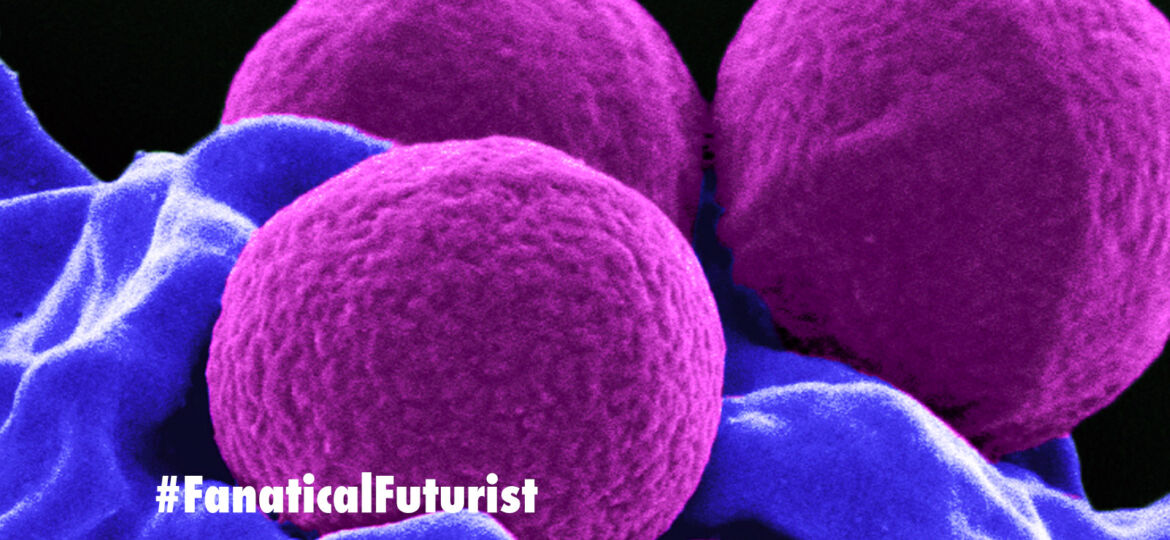

This week researchers unveiled a new kind of 3D Printing platform that, rather than using the traditional metals, plastics and polymers used by other 3D printers to print products, use ink made from living bacteria. The breakthrough now makes it possible to 3D print what the team are calling “miniature biochemical factories” that have individually tailored properties and capabilities that could be used to create a multitude of new, previously unimaginable products and biomaterials, all of which could potentially self-repair, and they’ve called their new inks “Flink” which stands for “Functional Living Ink.”

The teams new 3D printing platform lets users print a wide variety of different miniature biochemical factories and in a single pass they can use up to four finks, which are extruded from the printers jets as a hydrogel like substance, to create objects with different biological properties.

The hydrogels are made up from Hyaluronic Acid, long chain sugar molecules, and Pyrogenic Silica, and the team mixed the culture medium for the bacteria into the hydrogels so the the bacteria had everything they needed to survive and thrive.

During their first trial André Studart, head of the Laboratory for Complex Materials at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, and his colleagues Patrick Rühs and Manuel Schaffner used the bacteria Pseudomonas Putida and Acetobacter Xylinum.

The former can break down the toxic chemical phenol, which is produced on a grand scale in the chemical industry, while the latter bacteria secretes very pure form of nanocellulose, a pain relieving, moisture retaining, stable compound that’s already being used in smart bandages that help wounds heal multiple times faster than they would otherwise.

During the development of their finks the hydrogel’s flow properties posed a particular challenge. The finks had to be fluid enough to be forced through the pressure nozzle, and the consistency of the fink also affected the bacteria’s mobility. The stiffer it was, the harder it is for them to move, and if the hydrogel was too stiff then the bacteria were less productive. Similarly though, at the same time, the printed objects must be sturdy enough to support the weight of subsequent layers, for example, if they are too fluid, they collapse under the weight, making it impossible to print stable structures.

“The fink must be as viscous as toothpaste and have the consistency of Nivea hand cream,” is how Schaffner describes the successful formula, and as yet, the team haven’t studied the lifespan of the printed minifactories.

“As bacteria require very little in the way of resources, we assume they can survive in printed structures for a very long time,” says Rühs.

However, the research is still in its initial stages.

“Printing using bacteria containing hydrogels has enormous potential, because there is such a wide range of useful bacteria out there,” says Rühs, who blames the bad reputation attached to microorganisms for the almost total lack of existing research into additive methods using bacteria.

“Most people only associate bacteria with diseases, but we actually couldn’t survive without them,” he adds.

As for the applications of the technology, well, the researchers think they’re spoiled for choice, but for now they think the main applications will be in medicine and biotechnology, but other applications include 3D printed sensors containing bacteria that could detect toxins in drinking water, and printing filters that can be used to clean up disastrous oil spills.

First though it will be necessary to overcome the challenges of the slow printing time and difficult scalability. Acetobacter currently takes several days to produce cellulose for biomedical applications, but, naturally, the team are confident they can accelerate and optimise the process, and as for using bacteria to create biological minifactories? Well, as mentioned before, it opens the door to creating a wide variety of new exotic biomaterials and products that are either difficult, or impossible to make using today’s technology and no doubt the potential is limitless, especially if we start throwing in some genetically modified bacteria for fun…